Batu Ruyud Writing Camp | Tentang Primordial Loyalty Dayak yang Kuat (19)

Secara harfiah, istilah primordial loyalty berarti: kesetiaan pada sesuatu atau keyakinan akan sesuatu berdasarkan kepada ikatan primordial. Sedangkan face to face relations: relasi atau hubungan secara langsung, atau tatap muka.

Keduanya merupakan penciri utama suatu masyarakat tradisional, yang masih belum dipengaruhi atau diwarnai budaya asing. Relasi langsung menjadi ciri khas masyarakat adat tradisional, di mana komunitas bukan saja tempat berkumpul dan hidup bersama, melainkan juga public sphere, ala konsep Habermas. Di mana di dalamnya diwicarakan, disampaikan, didapatkan berbagai macam informasi terkait dengan perikehidupan suatu kampung. Kampung menjadi milik bersama, tidak ada yang tersembunyi.

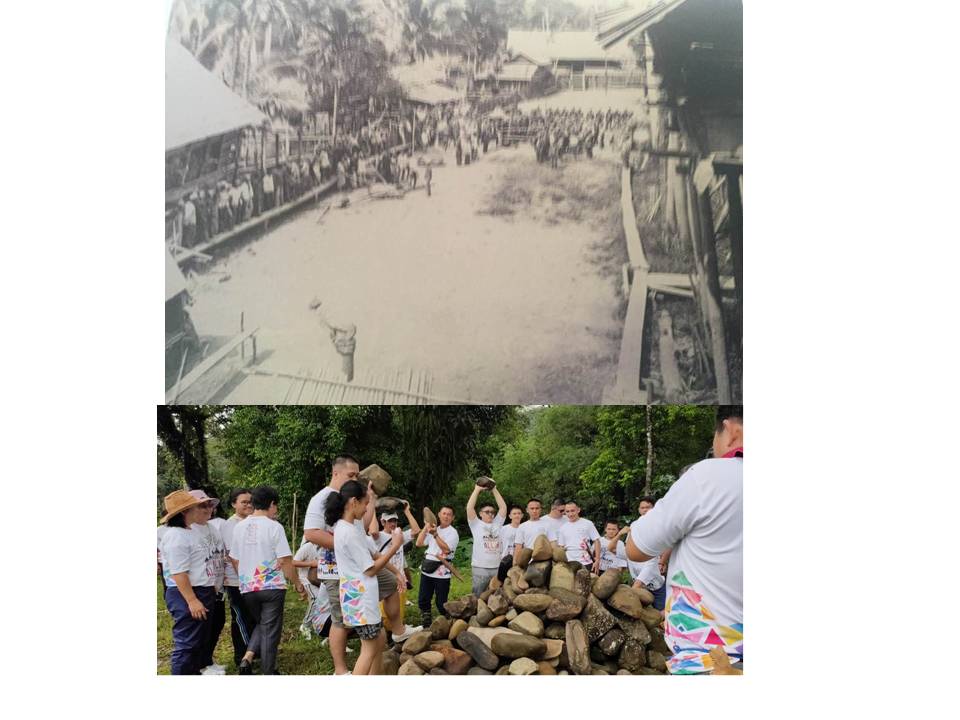

Apa yang membuat para peserta Batu Ruyud Writing Camp sudi datang ke Dataran Tinggi, the Heart of Borneo? Di mana letak kesamaaan spiritnya dengan para utusan Dayak se-Borneo yang berusah payah datang ke pertemuan akbar Tumbang Anoi pada 1894?

Dengan demikian, kontrol sosial di kampung, melalui face to face relations itu; demikian kuat. Seseorang yang masuk, atau menjadi warga mengidentifikasi dirinya dengan kelompok tersebut, sedemikian rupa, sehingga terbentuklah ikatan primordial yang sangat kuat. Yang lama kelamaan menjadi sebuah kekuatan sosial yang luar biasa.

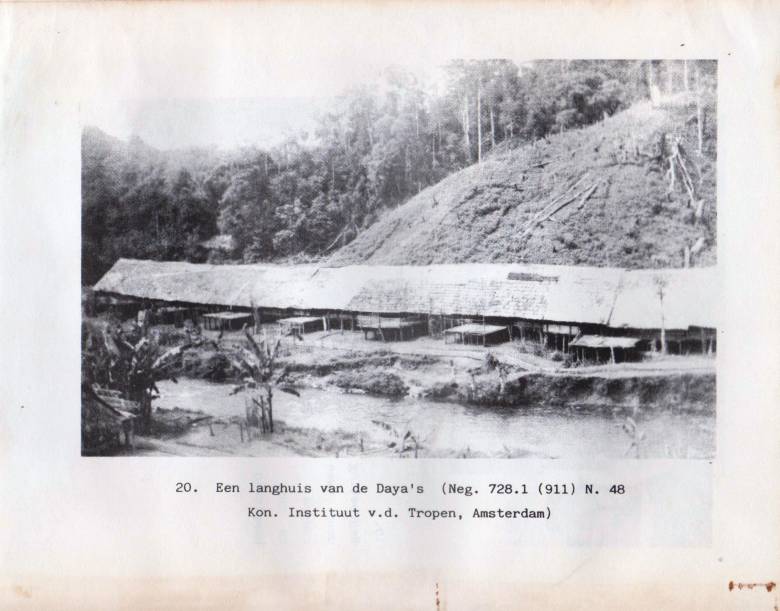

Bolehlah dibilang bahwa Web, juga medsos kita yang terhormat ini, public sphere zaman now. Huma betang, rumah panjae, lamin, rumah betang tak ubahnya Tumbang Anoi era Damang Batu tempat 3 bulan lamanya orang Dayak 152 suku undangan hadir. Dari Mei-Juli 1894.

Selain berdiskusi, mereka juga menancapkan tonggak baru: Mulai tumbuhkembangnya apa yang saya sebut “sensus Dayakensis”. Suatu unintended consequences yang salah dirancang Kompeni Hindia Belanda, yang telah dibahas pada narasi sebelumnya.

Bagaimana kontroler Barth dari Tanah Melawi dan de Heer dari Dayak Besar, kecele. Susah payah menyiapkan pertemuan, termasuk logistik yang dipusatkan di Banjarmasin. Naik kapal api berminggu minggu, dibadang hujan deras di hulu dan air bah dari Hulu Sungai Embaloh tak menyurutkan kehendak Barth untuk datang dari Melawi ke Tumbang Anoi.

Apa gerangan yang membuat para undangan-utusan sudi datang? Dan mau susah payah, menembus hutan belantara, menjelajah membelah medan yang sulit ketika 1894?

Apa yang membuat para peserta Batu Ruyud Writing Camp mau datang ke Dataran Tinggi, the Heart of Borneo?

Apa yang membuat para penulis pemula, dan top, untuk mau hidup, tinggal, bersama sebagai komunitas di “rumah literasi?”

Tak lain tak bukan: apinya literasi! Selain, tentu saja, yang akan dibahas pada narasi selanjutnya: mudah sekali “klik” dengan orang Kalimantan. Semacam ada kesamaan spirit.

Itulah, yang dalam khasanah ilmu etnologi disebut: primordial loyalty.

Hal yang membuat Dayak cukup berbeda dengan etnis lain adalah primordial loyalty yang kuat. Apa pasal? Boleh berbeda analisis. Sejauh yang saya trasi, dan kemudian menyarikannya dalam butir, terdapat 5 faktor mengaapa primordial loyalty ini berkanjang, dan terus hidup dan menghidupi Dayak di mana pun berada.

1) Budaya rumah panjang (betang, lamin, rumah panjai, radakng) membuat Dayak muncul belarasa yang tinggi, solidaritas, saling tolong, semua saudara, membantu yang dizolimi, rela meninggalkan pekerjaan yang lain demi tegaknya bonum commune (kebaikan umum). Sikap ini kuat, sedemikian rupa. Sehingga muncul pada waktu diperlukan, misalnya pada berbagai kasus, sebut saja beberapa yang besar dan berdampak seperti peristiwa di Sambas tahun 1999 [1], Sampit tahun 2001, dan yang masih segar dalam ingatan kita adalah kasus "penghinaan" orang Kalimantan secara komunal tahun 2022. Dapat kita saksikan dengan mata kepala sendiri, bagaimana Dayak bersatu, bahu membahu, secata kolektif menunjukkan bahwa mereka itu senasib sepenanggungan. Mengapa? Karena adat budaya, terbiasa hidup dan tinggal di rumah panjang ini.

2) Sensus Dayakensis (spirit Dayak) kental, yang dibangun sejak 1894 di Tumbang Anoi. Nota Kesepakatan untuk menghentikan 4-h (Hakayau, Habunu', Hajipen, dan Hatetek). Inilah "Hari Kebangkitan Internasional Dayak" --saya menamakannya demikian.

3) Responsif. Terbiasa hidup di alam, membuat orang Dayak selalu siap kapan dan di mana saja. Ke mana pun, alat-alat pertahanan diri (defensif) yakni perisai selalu dibawa. Demikian pula, alat menyerang (ofensif) yakni mandau dan sumpit tidak pernah tidak dibawa. Kapan waktu kedua jenis alat itu digunakan, bergantung pada situasi-kondisi.

4) Survive yang tinggi. Orang Dayak terbiasa hidup di alam bebas. Bahkan, dilepas di hutan saja, mereka bisa hidup. Makanan dan buah-buahan yang dapa dimakan, dan yang beracun, mereka mafhum.

5) Insting yang luar biasa. Ini dilatih. Berburu salah satu latihan yang sempurna. Sedemikian rupa, sehingga orang Dayak --seperti diberitahu dari langit-- dapat mengantisipasi apa pun keadaan. Melakukan dan tidak melakukan pada timing yang tepat.

Kiranya, primordial loyalty ini cukup dulu dibahas. Kita sisakan untuk narasi yang berikutnya,.

(Bersambung)

Catatan akhir:

Ketika Jenderal (Purn.) Agum Gumelar, Gubernur Lemhannas, saya pernah presentasi topik ini di aulanya. Dihadiri para perwira dan *, juga akademisi dan pemerhati. Bersama saya narsum adalah Manuel Kaisepo tentang Papua dan seorang tentang Aceh. Lalu pemikiran saya kirim koran The Jakarta Post dan dimuat sbb:

The Solution to the Sambas Riots

The Jakarta Post, Jakarta | Opinion | Tue, April 20 1999, 7:04

By R. MasriSareb Putra

JAKARTA (JP): Many believe the recent riots in Sambas, West Kalimantan, are similar to those breaking out in other parts of the country, including the one in Ambon, Maluku, because they seem to resemble each other in theircasus belli and their escalation patterns.

However, the backgrounds and the root cause of the riots are obviously contradictory.

Some parties have alleged that ""invisible hands"" involving international provocateurs have played a role behind the scenes in Sambas. Such an allegation is groundless and exaggerated because even before the word ""provocateur"" began to be popular in this country, similar inter-ethnic rioting had occurred in Sambas; the latest riot was the ninth since 1967.

This article seeks to provide the background to the Sambas riot, explore its root cause and offer a solution to the problem at hand.

As for the motives of the conflict, there are, at least, five possible reasons for the outbreak of riots on March 16.

First, the riot in Sambas was an accumulation of problems relating to theintegration of the indigenous ethnic group and Madurese migrants. Prior to the recent riots, conflicts between the two groups occurred several times; the last outbreak in 1996. Efforts to bring about reconciliation were made repeatedly.

Second, it is only a coincidence that the two conflicting ethnic groups profess different religions. Some people consider the conflict as resultingfrom antagonism between the two religions. In fact, religions are in no wayconnected with these inter-ethnic conflicts, as religion and ethnicity are two separate things.

Third, the conflict may have been provoked by a third party who, knowing the potential for conflict in the area has long been present in Sambas, fishing in troubled waters.

Fourth, it is always likely that remnants of the Security Disturbance Movement -- a rebel organization crushed by the Armed Forces together with local people from 1960 to 1970 -- remain in existence.

Fifth, this conflict is indeed brought about by development excesses. Thegovernment concentrated its development undertakings in Java and has, in a way, neglected the regions. Unfortunately, the people in West Kalimantan are well aware that while their province is Indonesia's fifth largest foreign-exchange earner, it is the third poorest province in the country.

The first and third causes may be correct, while the fourth, which soundsreasonable, is no longer relevant. It is the fifth cause which is most likely (and almost always the case) to trigger conflicts. Integration between migrants and indigenous people has not been running smoothly and isalso a contributing factor.

It is widely known that West Kalimantan is rich in natural resources, which have lured businessmen to operate mining, agriculture and forestry ventures. Unfortunately, almost one third of the province's total area of 146,700 km2, has become barren land as a result of irresponsible tree felling.

Indigenous people understand that land tilling -- practiced for generations -- cannot be the reason for the damage to the province's forestry areas. Unfortunately, the indigenous people have often been accused of harming the land.

In fact, with their centuries-old traditional farming methods, the indigenous people know how to take care of the forests. They are aware they cannot open up farming land in the same area for 15 years, because by then the trees will have grown and the fertile soil layer will have become thick enough to farm again.

In short, indigenous people are well aware that nature is part of their lives and must therefore be conserved. They understand it is of utmost significance to keep a balance between human beings and nature. To indigenous people, damaging nature is tantamount to damaging human beings. Therefore, nature-damaging acts are customarily punished.

Unfortunately, forest concessionaires do not understand that indigenous people are close to nature. By damaging nature and felling trees, be they big or small, forest concessionaires have dashed to pieces indigenous people's future.

Recently, the situation has deteriorated because the control of tree felling in West Kalimantan has weakened. It is natural that forest concessionaires vie for control over land, so that in many cases it is locals who are victimized.

When forest concessionaires are busy using theirchain saws to fell trees, indigenous locals, who have felled only one tree to meet their household needs, are accused of stealing. This is indeed a portrait of injustice.

West Kalimantan is also endowed with abundant gold deposits. Since the 17th century, Chinese immigrants have mined gold in Sambas. They first camethere at the request of the Sultan of Sambas, Aboebakar Tadjoedin I. Once, a dispute among gold miners in the area triggered a civil war.

West Kalimantan's coastal area, from Singkawang to Pemangkat, Tebas and Sambas, is famous for its fertile soil. Tagged ""a rice granary"", the area also produces the famous Pontianak oranges.

Sambas is also known as a copra and pepper producer, two commodities which, when sold to Malaysia after they are processed, bring in lucrative proceeds.

It is interesting to find out who owns these mining, forestry, agricultural and estate companies. Unsurprisingly, the enterprises are controlled by former president Soeharto's family members and their associates. Tommy Soeharto, for example, once monopolized the sale of Pontianak oranges and Soeharto associates control gold mines in Monterado and Budok.

Indigenous locals have lived in an oppressive atmosphere brought about byyears of exploitation and injustice. During the New Order era, protests against encroachment upon one's property and efforts to maintain private ownership were considered acts against the government. No one dared to stand up against this unjust allegation.

During the New Order era, the government always discovered means to suppress the anger of indigenous locals in Sambas. The suppressed anger wasa sort of time bomb; once the anger could be no longer suppressed, it foundits own target and not necessarily rational ones. Anything could be targeted as long as the anger could be channeled.

Unfortunately, those targeted are Madurese migrants. In fact, they have done nothing wrong. What is wrong is the stereotypical image and opinion built about them. To indigenous locals, Madurese migrants are often viewed as people sent by the government to usurp West Kalimantan's agricultural and mining assets. They are regarded as symbols of a new colonialism whichmust be opposed.

The question is: ""Who constructed and inflated this image of Madurese migrants? Provocateurs?"" If yes, who are they and what are their interests? Even if provocateurs were in Sambas and fanned the riots, the authoritiesshould have been able to localize the situation in order to prevent the trouble from escalating.

Local leaders are well aware that riot-related matters must be approached culturally through customary laws. A security approach, introduced by the government on several occasions, will never solve the problem.

However, such a cultural approach was not adopted when a group of Madurese migrants took revenge upon a group of Malays, killing a Dayak. To the Dayaks, intentional bloodshed and deaths are taboo. In such cases, theyapply the traditional law of ""an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth"".

But this traditional law can always be exercised in a different manner according to the local custom. For example, a head, can be replaced by another object as long as a special rite is performed for this purpose.

Unfortunately, security apparatuses were too slow taking action and were unresponsive to this matter.

Failure to settle this issue on the basis of customary law made the criesof war unavoidable. The chief of the Dayaks issued ""a red bowl"", indicatinga declaration of war, which had to be passed on to the war commander of each tribe. As soon as the red bowl was received, all Dayaks joined forces to fight against the attackers.

This kind of war will never be stopped unless a rite is held to recall the spirit of war. In the case of the recent riot in Sambas, this rite should have been held immediately to prevent the riot from escalating and spreading to other places.

In the short term, a rite to recall the spirit of war must be immediatelyperformed. Then, as is customary, ethnic groups embroiled in the dispute should draw up, agree to and pledge to comply with a peace pact.

In the long term, the central government should not repeat past mistakes.For example, local leaders (governors and district heads), should be selected among the best candidates in the region, not from candidates appointed by the government.

Last but not least, the government should not try to once again avoid responsibility for its actions. The government must punish those exploiting the natural wealth of West Kalimantan. It should not scapegoat migrants of a certain ethnic group; these migrants are innocent.

*)The writer, born not far from Sambas, is a Dayak ethnology researcher.